The Zika Virus and the Art of Drinking Water Supply

The rapid spread of Zika virus infections across South and Central America has raised concern among public health professionals in record time. Only weeks after the first reports about the virus and its neurological effects emerged, the World Health Organization declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, opening the way for a coordinated international response. Zika had become a global public health emergency.

The Zika virus has the potential to affect health in all its aspects: physical, mental and social. The focus has been on its link with microcephaly, a developmental disorder reflected as reduced growth of the skull and brain. The prognosis of newborns with microcephaly is poor brain function and a significantly shortened life expectancy.

The other suspected link is that between Zika virus infection and the frequency of an auto-immune disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome. This causes paralysis that can be from mild to life-threatening. Many cases are fully or partially reversible, but nevertheless a heavy burden on individuals, their family members and the health services.

Ten years ago I witnessed Guillain-Barré syndrome first hand in a 40-year-old Costarican nephew. A rapid onset paralysis (a matter of 36 hours) would have resulted in certain death if his condition had not been recognised in time. He was on artificial breathing in intensive care for weeks. He went through extensive rehabilitation. Sadly, he never fully recovered. Joseph Heller, the author of Catch 22, contracted Guillain-Barré syndrome and wrote a book about the experience entitled Not a laughing matter. Not a laughing matter, indeed.

So where does drinking water supply enter into this story?

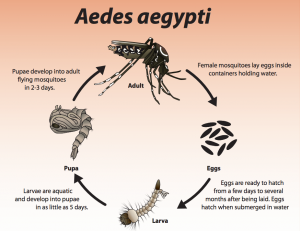

Mosquitoes of the genus Aedes have been known to transmit viruses for decades. They were behind the outbreaks of yellow fever among construction workers building the Panama Canal, they transmit the dengue virus that started its globalisation from South East Asia in the 1950s, and more recently they gained ill repute by transmitting Chikungunya virus.

Mosquitoes are particular about the aquatic environment where they lay their eggs. Aedes mosquitoes originally used small water collections in the leaf axils of plants. Human settlements, with their many small water collections in and around the house, provide fertile breeding sites. Flower vases, air conditioners, roof gutters, drains and, ironically, cemeteries where people regularly put flowers in vases, are all significant sources of Aedes mosquitoes. Importantly, domestic drinking water containers are also a preferred breeding site.

What can water and sanitation professionals do to reduce Aedes breeding to help prevent the spread of Zika virus?

Zika virus is one micro-organism; dengue virus another. We have neither drugs nor vaccines to protect against or treat the diseases they cause. In the absence of other public health measures, our target is the vector. The virus is new, but we have known the vector for decades.

Insecticides will not bring a permanent solution. Treating all these breeding places is mission impossible. Fogging houses with insecticide to kill adult mosquitoes remains in many instances an after-the-fact, cosmetic operation. Sooner or later insecticide resistance will emerge. Treating drinking water containers with insecticide to kill mosquito larvae is often socially unacceptable.

The question we need to ask is, why do people store drinking water at home? They do either because their drinking water source is a well or a stand pipe, or because their piped water supply is unreliable. This creates an important opportunity for the providers of drinking water to take an active role in the prevention of mosquito vector breeding.

First, embarking on a massive information campaign about the risks of storing drinking water at home, and on measures to make storage safe. Container design with netting is an important though not always sustainable approach. Second, by accelerating improvements in water services, enhancing reliability and eliminating the need for household water storage. And thirdly, by training operation and maintenance staff to serve as extension agents in educating customers on making their homes vector-breeding free.

Sanitation service providers can complement these efforts. Aedes mosquitoes have no link to toilets, latrines and sewage drains. But they are linked to the lack of environmental sanitation at large. Systematic and regular garbage collection is a first step. Advising community leaders on how to organise clean-up campaigns is another. Community awareness will provide the social pressure on members who do not cooperate and create risks for the entire community.

All this sounds simple on paper. It is challenging when it has to be applied in favelas and other informal settlements. Yet, it is the only sustainable solution to the problem. Water service providers and regulators can work together for a safer human environment: by improving their services; by informing their customers; by assisting informal service providers in risk management; and by supporting clean-up campaigns in communities.

There are many myths evolving around Zika virus and government efforts are being undermined by conspiracy theories. Yet, we know the enemy and its weak spots. We know the costs of inaction to the health sector (let alone the human suffering) will be colossal. Water and sanitation professionals can make a significant contribution to solving the problem. Investments made now in improving services will be largely offset by the reduced financial burden of widespread disease and infirmity. It’s time to act.

Robert Bos worked for the WHO for 32 years. From 1983 to 1990 he worked on environmental management for vector control in the Organization’s Vector Biology and Control Division. Between 1990 and 2013 he worked in the Water, Sanitation and Health Unit, the last four years as its Coordinator.

Images courtesy of the Centres for Disease Control