Collaboration for a Water-Wise World | Part 2

Water managers and the myth of best practice

Managing urban water challenges lies at the heart of a sustainable future and drives my work in the sector. As a coach, I talk to many managers and leaders grappling with difficult water projects, learning from both their successes and their failures. In my blog of November 2018, I shared some of the things I’ve learned about mindsets to enable great collaboration. In this blog I will explore one specific element of mindset for water managers.

The mindset I strike often is the idea that we must apply ‘best practice’ to our projects. But this can be a trap for us all. I have learned that when facing complex, multi-party water challenges, the myth of ‘best practice’ can limit, rather than support, progress.

What do I mean? There are many urban water and sanitation initiatives around the world, and from these are emerging many models and frameworks for how to achieve water outcomes. A good example is Sanitation 21, published by the IWA and partners in 2014. This document lays out a comprehensive, detailed ‘map’ for improving sanitation in the developing world. It includes process flow charts and step-by-step instructions and is explicitly an attempt to reflect best practice.

Its great strength is its careful detail about how to go about sanitation projects. Yet, I believe that without a collaborative mindset, this detail can also be a great weakness.

If you are building a water treatment facility, you will find a best-practice, step-by-step guide very useful. You know what the problem is. You know what the endpoint will look like. And if the construction plans have already been proven, they should work just as well here. But changing the long-term sanitation practices of a community is a qualitatively different type of problem. In this situation, there are multiple variables, only some of which we can be aware of and lots of players with different drivers and concerns. There are unique geologies, geographies, governance practices, climatic conditions, budgets and habits. There are social interactions and practices that we can’t possible understand completely. In short, every project is unique and what worked last time may not be appropriate here. In this context, if we attempt to rigidly apply our ‘best practice’ approach we are very likely to fall short.

A key weakness of the best practice myth is that by focussing on delivering a program we greatly increase the likelihood that we are doing this program ‘to’ the people we most need to work ‘with’. This is where mindset comes in. If I feel I have a clear, smart process to follow then my task is to apply it to the best of my ability. But if my belief is that my process map is a hypothesis I bring to the table, rather than the best practice answer, I will think and act differently. I will see stakeholders as co-designers of process. I will listen as loudly as I speak. I will be prepared to put my process back in my pocket and experiment together with this community.

Doing so will encourage innovation from the very people who are impacted by the problem in the first place, whereas doing my change process to them will likely drive them away.

But giving up my process is hard. Sharing control and taking risks makes me feel vulnerable. Isn’t it easier to stick to a proven pathway?

Easier, yes. But that is the trap of the best practice mindset.

Want to read more about how to successfully deliver complex projects and avoid the trap of best practice? You can find more at www.twyfords.com.au, or try these great resources:

Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders 1st Edition

Jennifer Garvey Berger, Keith Johnston

Stanford University Press 2015

A leader’s Framework for Decision Making

David J Snowden and Mary E Boone

Harvard Business Review Nov. 2007

The Power of Co: The smart leaders’ guide to collaborative governance

Vivien Twyford et al

Twyfords 2012

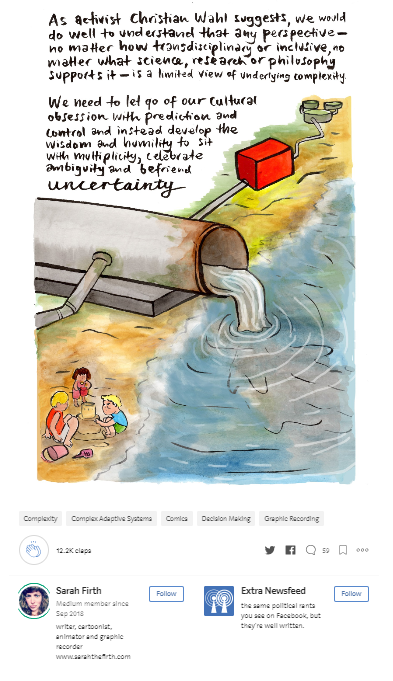

Making sense of complexity: graphic art

Sarah Firth

ExtraNewsfeed 2017