Nature for cities or cities for nature?

“We cannot solve our problem with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Albert Einstein

We’ve all heard about thinking out of the box… But it’s easier said than done. A few days ago I was pushed outside my box at the event organized by LeMonde Cities, featuring architects and urban planners on the topic of “Can nature humanize our cities?” inspiring cities to change their paradigm and embrace that they are part of nature rather than users of it.

My box is water: urban water systems, water security, and the impacts on water of climate change. From that box, the challenges appear to be:

- performance of treatment,

- how water and wastewater can contribute to the circular economy,

- the need for more robust systems that can operate in a wide range of conditions, and

- the need for resilience to prepare for changes that go beyond the capacity of the systems.

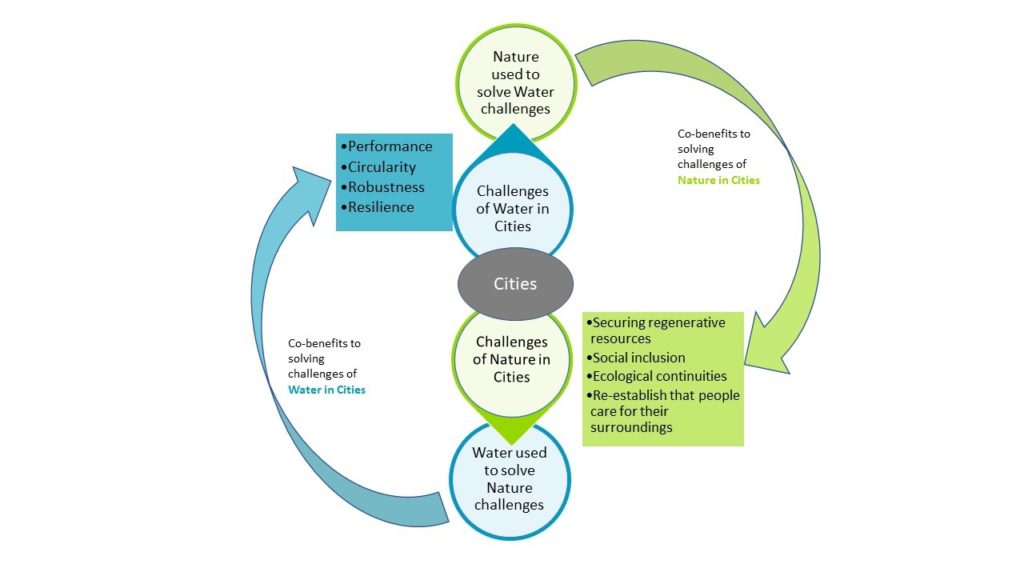

Solutions to these problems can be technology-based or nature-based. Water professionals are increasingly seeking out nature based solutions (NBS), yet get stuck in a technical perspective: using plants to retain stormwater or protect a water catchment upstream of the city. NBS are implemented to the benefit of the water systems with some liveability co-benefits. The mindset remains to use nature rather than think the city as part of nature.

Listening to the perspectives on nature and cities from philosophers, architects, and geographers at the LeMonde City event, I reevaluated my definition of Nature as “the healthy relationship between all living and non-living things”. All living things include people – all urban dwellers are therefore part of nature; non-living things, such as topography, geology, and water flows, form the basis of all built environments, and all together these are the settings for healthy relationships between the living.

The first human settlements were built to respond to the primary need for protection from cold, heat, rain, danger, and were built to ensure water and food security. The location of the settlements was driven by the “non-living things” and the built environment promoted balanced relationships between people and nature, supporting ecosystems living in harmony.

As the settlements grew, a disconnect began to form between humans and nature. Fast forward a few thousand years, and now food is brought in by suppliers, water is delivered by unseen pipes, and waste is taken away by pipes or trucks. Cities have transformed into resource extraction engines, dehumanized and denaturalized in many cases.

With this in mind, if we come back to the challenges from the standpoint of a water professional, I can see opportunities to solve these challenges by thinking of NBS not only as more green, but also as more human. People’s behavior is part of the solution, as it can reduce the pressures on performance, enhance circularity, as well as increase robustness and resilience. Behavior impacts the design parameters of our systems, for example:

- In Morocco, we design water supply for 70 L/pers/day, whereas in many American cities we design for 300 L/pers/day.

- In Europe we design for 60g of BOD5/pers/day for the organic load in the wastewater, whereas in the US we design for 80g of BOD5/pers/day (mostly due to the use of garbage disposal in households kitchen sinks); or in Thailand we design for 40g of BOD5/pers/day as households have on-site septic tanks and only dispose of the grey water and the septic tank overflow in the sewer system. [Note: BOD5 is an indication of the organic waste concentration in the wastewater]

Behavior also impacts the performance of our systems, for example:

- People dispose of medicine, chemicals, grease and/or wipes in their household drains, creating massive problems in pipes and treatment systems.

- When water security is threatened by drought, people can reduce their consumption to maintain the systems in operation, as we saw in Cape Town in 2018, or in Australia during the Millennium Drought.

Now let’s step out of “the box which created our problems” and rather than just look at how nature (including people) can help solve water problems, let’s look at what nature needs to recover its balance. Can we enter a virtuous circle where water contributes to a healthier Nature, which in turn solves water issues, but also social issues, pollution issues, and many more? Can water be a tool, an entry door, to recreate emotional connections between people and make them part of nature again?

Sofia De Meyer, Founder of Opaline and thought leader in circular economy, shared “we cannot protect something well if we are not emotionally connected to it.” Visible water in urban public spaces, communication on where water comes from and how much is left in the reserves, or water quality in bathing areas, are all ways to recreate the emotional connection to nature so that our society takes an active role in protecting our planet.

Photo credit: India Today

It’s about people recovering their position within nature, so that the primal balances are recovered, and not only for effective water management, but also for many other societal challenges. Nature for cities or cities for nature? The answer is both, so that we achieve “Nature Cities”, cities with a built environment that foster healthy relationships between people, plants, animals and their surroundings.

I encourage water professionals to meet urban planners and architects and work together in embracing water in cities. I look forward to this opportunity at the Urban Future Global Conference in Lisbon, Portugal, on 1-3 April 2020.

top-photo: Singapore Nature City. Photo Credit National Geographic.