Lessons from urban water reform, the Australian story

Starting a governance reform process?

‘Governance reform’ is a catch phrase that is often used by water leaders as a panacea to fix the many ills afflicting a water sector. From a management perspective, reforms can be difficult to pin down and even more difficult to know where to start. In some ways, there’s no single correct starting point. The OCED principles for good water governance, while offering sound guidance, don’t necessarily help you to know how to get there. Another good starting place is to look at what someone else has done and learn from their experience.

Urban water supply utilities in Australia are recognised as global leaders in delivering efficiency, productivity and security of supply, as well as upholding robust environmental standards. This view is backed by a recent Asian Development Bank report, the Asian Water Development Outlook. This tracks five key dimensions of water security, and identified Australia as delivering effective urban water services. However, this level of service has not always been the case, and the history and process of reform has not been comprehensively documented.

To address this, the International Water Centre and the University of Queensland partnered with the World Bank to document lessons from the Australian urban water reform processes. Australia’s story provides useful lessons for other countries that may be embracing an urban water reform process.

Figure: Outhouses, Brisbane 1960’s. Current water and sanitation service standards in Australia have come a long way in the last few decades. Source: QUU

Bottom up top down

The report tells the story of urban water reforms in Australia from the late 1970s onwards, documenting changes brought about through three waves of reform. It highlights the drivers of each stage, and the processes and major outcomes from each stage.

The first wave emerged from the bottom up. A number of utilities responded to local challenges associated with water scarcity and financial pressures, often linked with inefficient property value-based charging. In Western Australia in the late 1970s, declining inflows in the city of Perth led to a two-tiered pricing system for urban water consumption. On the East coast, Hunter District Water Board, facing similar water shortages and financial pressures, introduced user-pays pricing but went further by reducing water allocations.

Another milestone in this phase took place in the State of Victoria, where a 1983 Public Bodies Review Committee led a wide-ranging and bi-partisan parliamentary review of water management across the state. This lead to the aggregation of some two hundred water authorities to fewer than twenty. This showed other states and the national government what could be achieved in bipartisan agenda setting.

Recognising this success gave the national government confidence to step in and lead a second wave of reforms focused on consolidating earlier lessons and bringing those lessons to scale. An economic downturn became a key driver for an unproductive and costly water sector. National-led reforms were coordination by the Council of Australian Governments, which adopted a National Competition Policy along with a range of initiatives including a reforms framework, federal incentives, benchmarking, and investment in water knowledge and expertise.

States adopted the reforms in different ways, but they collectively led to a three-staged approach to restructure utilities and agencies: aggregation (or disaggregation in some cases); separation of responsibilities including clarification of service delivery roles often through corporatisation; and the establishment of professional regulators to provide a platform for commercialisation.

A third phase of reforms was driven by the Australian millennium drought, which saw water scarcity reach crisis point. In response, the National Water Initiative was established and, while largely focused on the need to deal with over-allocated or stressed water systems, this phase brought reform on pricing for water storage and delivery, and increased focus on demand management.

Leadership for reforms

While some regard economic regulation as the most powerful intervention of all the reforms over the last three decades, it’s also clear that reform is not just about structures. The processes and people involved were key for enabling change.

Building support for national reforms involved a range of champions. In the 1990s, Sir Fred Hilmer led the process of ‘cherry-picking’ the best and most relevant reforms from around the country. He merged these into a coherent reform strategy, the Water Reform Framework. Importantly, he had the resources and support to overcome any observed barriers to reform.

At the institutional level, the importance of having individuals who possess “an understanding of how to interact with the political and the public, as well as the paying customers, and know how to treat them as stakeholders was critical.” Local leadership was also critical, leading the evolution of organisational culture and ensuring the right diversity of skills sets to address the challenges and opportunities presented by urban water reform.

Political leadership was also vital. Reforms could only be achieved through negotiated outcomes with stakeholders and communities that were politically feasible. This influenced how reforms progressed and the pace of reform over time, emphasising that water reform is an iterative process. Some states could move faster, depending on the readiness of stakeholders.

Recognising the need for different paces of reform, and that no one size fits all, are important lessons from the Australian experience. The Australia reform story highlights how a set of principles were used to engage states and territories around a shared focus, yet allowed different approaches and structures to emerge in different jurisdictions. Nearly all delivered the targeted outcomes of efficiency, productivity and security of supply, as well as upholding environmental standards.

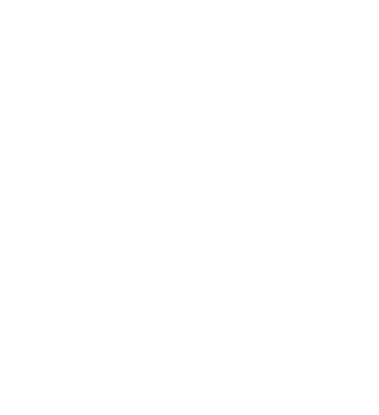

Figure: Map of urban water utilities in 2016. Source: BOM

Why it is important to share these lessons now?

While not perfect, urban water service delivery in Australia remains richly varied and is the envy of water practitioners struggling with inefficiencies, lack of clear rolls, unclear pricing structures and conflicting policy directions. The global focus on delivering universal access under the Sustainable Development Goals recognises the need for global partnerships to enhance policy and institutional coherence for sustainable development. Australia has many lessons it can share with the world.

The World Bank did not engage in this project to document this story for Australia’s sake. It saw it as an opportunity to assist countries with similar legal frameworks going through similar transitions. For example, India and Australia are both federations. In India, as with Australia, responsibility for water supply is devolved to the states, with local authorities mandated to provide effective water and sanitation services while the national government assumes responsibility for funding and oversight for the national interest.

While water reforms in Australia involved six states and two territories, India has 29 states and seven unions. Not to mention a population of approximately 1.3 billion, some 55 times larger than that of Australia. It’s clear that the scale of the challenge facing the Indian urban water sector vastly exceeds the challenges that faced Australia at any stage of its water reform history.

It’s also clear that any lessons from Australia can only contribute to part of the Indian reform story. This does not diminish the value of considering which of those structural, institutional, organisational and individual factors in Australia influenced change, or the sequencing of change, and how these were applied at different levels and across different states.

Partnering with Indian stakeholders to both understand the demand for reform, and to explore how individual or collective lessons can be translated into opportunities, is the next stage to drive reform that enhances policy and institutional coherence – a critical step to support the sustained delivery of water services for all.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Water Reform and Governance Online Training

The International Water Centre is offering a six-week online training course and interactive learning experience, 23 August – 27 September 2017.

The course draws on practical examples to demonstrate how water reform processes are successful when they are context driven; inclusive of direct and indirect users of water; take a full water cycle approach to reform; and consider multiple societal outcomes. The course concludes with a look at the limits to current reform processes and explores what else should we as water professionals be considering.

You can find more information at www.watercentre.org , by emailing training@watercentre.org or by downloading a brochure

The Australian Urban Water Reform Story: with Detailed Case Study on New South Wales is published by World Bank and can be downloaded here: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27532