Catchment Protection through collaboration

Nature-based solutions have significant yet untapped potential in Ghana. Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL), the main provider of urban water supply in Ghana, recognises an important role for natural infrastructure in the attainment of Sustainable Development Goal 6: to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. As regulatory frameworks for managing water resources continue to be strengthened, GWCL’s strong motivation to apply nature-based solutions in catchment management is clearly manifested through their active engagement with water resource agencies and users across the country.

“Regulatory frameworks to support catchment management are in place, but not effectively enforced for compliance, which has led to water quality degradation at most of the utility’s abstraction points. Compliance needs to be ensured to protect public health, water security and reduce production costs for the water utility”, as narrated by Mark Ayertey, a Water Quality Officer at Ghana Water Company Limited.

GWCL‘s raw water supplies are derived from rivers, lakes, reservoirs and groundwater, which need to be sustainably managed to meet the demands of an ever-growing population. The amount of water availability in Ghana can change drastically from season to season. As a region vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, GWCL is aware that their hydrologic systems face the increasing threats of variable rainfall and recurrent droughts. The susceptibility of their water sources is exacerbated by the damages caused from human activity, such as illegal logging and mining, deforestation, pollution from liquid and solid waste disposal and poor agricultural practices.

These harmful activities degrade the vegetative cover along the banks of water sources, leaving them even more exposed to the impacts of climate variability. Poor water quality and insufficient quantity have direct implications for GWCL’s operations. GWCL faces critical water quality challenges caused by pollution from effluent discharges and the poor siting of waste management areas. In the past, the utility was forced to suspend operations at their Nsawam treatment plant (outside of Accra) for several months due to the high costs of treating the turbid raw water.

Population growth, economic development and changing consumption patterns are placing strains on Ghana’s water supplies. GWCL’s motivation to tap into ecosystem services as a means of regulating and improving water quality is driven by the potential for high rewards. Integrated approaches to water management have proven successful over the past few years, encouraging GWCL to prioritise collaborative efforts with water agencies and improve awareness on the topic of NBS.

A series of reforms to Ghana’s water sector in the 1990s decentralised responsibilities for water and sanitation provision. The reforms aimed to improve coordination and collaboration throughout the water sector by delegating responsibilities across several agencies: the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was tasked with ensuring water operations would not harm the environment, the Water Resource Commission (WRC) would provide regulatory and water resource management oversight, and the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) would establish tariffs and quality standards for the operation of public utilities. The Community Water and Sanitation Agency (CWSA) was established to manage rural water systems and GWCL was delegated responsibility for urban water supply (GWCL, 2019).

Establishment of Water Resource Commission/Basin Boards

The establishment of bodies such as the WRC have improved cooperation in Ghana’s water sector, an important element for the future growth of NBS. The WRC acts as the central coordinating body for water resource management at both a national and local level.

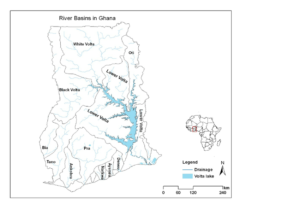

At the national level, it is focused on strategic engagement with major water users like GWCL and CWSA and water-related regulatory institutions, data management institutions and NGOs. At the decentralised level, the Commission operates through an administrative framework with coordination bodies known as River Basin Boards. Thus far, WRC has supported the institution of 7 River Basin Boards, which are composed of selected stakeholders with key roles in addressing the water resource challenges of each basin. WRC contributes to the development of targeted action plan interventions for the rehabilitation and preservation of these important water bodies. This is accomplished through capacity building workshops, public meetings and awareness-raising efforts.

Ghana’s River Basin Boards have been effective platforms for stakeholders to identify and propose solutions to the context-specific issues in each region, ultimately working toward the development of an integrated water resource management and investment plan (WRC, 2019). Collaboration with River Basin Boards has provided an entry point for GWCL to participate in catchment protection efforts and contribute to the developing management plans.

As a major water user, GWCL has a representative on the WRC board and each River Basin Board in the country. This affords the utility a level of representation in every WRC project, as well as a voice in the formulation of laws and policies. The close working relationship between utility and regulator is further evidenced by the establishment of an internal department in GWCL, specifically tasked with liaising with WRC to prevent pollution around the utility’s raw water abstraction points. Another example of coordinated efforts toward catchment management is illustrated in the water fee structure.

The first regulation developed and adopted by Parliament under WRC was the Water Use Regulations Legislative Instrument (L.I.) 1692 (2001). It serves to regulate water use permits or water rights for various water and allocates fees toward catchment management activities including reforestation of degraded water sources, public awareness and education, and ecological monitoring.

The WRC can incentivise the use of NBS for water management through existing laws and regulatory frameworks. For example, Section 35 of the Water Resources Commission Act 522 stipulates that regulation can be made for the protection of watersheds or for preserving existing uses of public water (WRC, 1996). In addition to using existing mandates, WRC has also pursued innovative policies.

In 2004, the WRC partnered with the Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing, along with other stakeholder institutions and interest groups, to devise a consolidated Buffer Zone Policy that would address environmental degradation in the region and outline objectives for more sustainable practices (Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing, 2013). The Buffer Zone Policy represented an important step toward a national policy on buffer zones for river basins by instituting a set of procedures to control harmful catchment activities. The policy has not been formally enacted into legislation, which complicates efforts to enforce compliance.

|

|

Students, GWCL staff and WRC staff plant trees within the catchment of Barekese dam for World Water Day 2017 ©WRC

While the frameworks advance sustainable approaches to catchment management, GWCL attests that lack of enforcement means water quality issues often remain unsolved. ‟The key issue is enforcement for compliance. Water quality challenges are prolonged as a result of limited or weak enforcement of regulations on effluent, waste and wastewater management, as well as other harmful catchment activities″ explains Mark Ayertey, Water Quality Officer for GWCL. There are indications that enforcement efforts are taking root at a local level. For example, registration of water users under section 11 of the Water Use Regulations LI 1692 of 2001 is carried out by the local authorities, who additionally monitor encroachment and improper waste disposal. Nevertheless, without formal legislative backing, enforcement is dependent on strong local governance structures.

GWCL recognises a barrier to widespread adoption of NBS in Ghana is the lack of understanding and confidence in these approaches at both a policy level and within the utility. Overcoming this barrier requires working closely with River Basin Boards to increase knowledge about how NBS can improve water management and the associated costs and benefits when compared to grey infrastructure. GWCL has creatively turned to Water Safety Plans (WSP), an approach of managing water supply from catchment to consumer, to illustrate how NBS can support the delivery of safe and secure water supplies. GWCL has developed WSPs for a number of their treatment plants and actively engages with customers through the implementation of these plans to demonstrate impact. A conscious effort to secure the participation of different community stakeholders, local authorities, and non-governmental organisations, and educational institutions will be necessary to accelerate adoption of NBS.

Increasing public awareness of water quality issues, combined with more effective enforcement of existing regulations could have a significant impact on the water quality challenges facing GWCL. To reach this point, GWCL must focus on gathering reliable water quality data to support improved management and protection as well as design targeted public engagement strategies. WRC is also considering ways to improve education and awareness around water issues. They currently engage with the community through durbars, gatherings of community elders and residents for educational, awareness-raising or communication purposes, and additionally rely on stakeholder meetings or workshops and existing advocacy learning platforms. Continuing to collaborate with different community stakeholders, local authorities, NGOs, and educational institutions is critical for the long-term sustainability of NBS in Ghana.

This spotlight is part of a publication of utility case studies intended to shed light on the opportunities and challenges facing regulators and water utilities in their efforts to incorporate nature-based solutions into water management.

REFERENCES

GWCL (2019) History of Ghana Water Company Limited. https://www.gwcl.com.gh/gwcl_history.pdf (Accessed May 19th, 2019)

GWCL (2019) Ghana Water Company Limited. https://www.gwcl.com.gh/company_profile.html (Accessed May 19th, 2019)

WRC (2019). Water Resources Commission http://www.wrc-gh.org/ (Accessed May 17th, 2019)

Ministry of Water Resources Works and Housing (2013). Riparian Buffer zone Policy for managing fresh water resources. http://www.wrc-gh.org/documents/acts-and-regulations/ (Accessed May 20th, 2019)

WRC (1996) Water Resources Commission Act, 1996. http://www.wrc-gh.org/documents/acts-and-regulations/ (Accessed May 20th, 2019)